According to John Anderson Miller (Fares Please, N.Y., 1941 — the definitive history of urban transportation), the British coach builder George Shillibeer built a “vehicle” for a Paris operator in 1825, the earliest known date for the omnibus, introducing fixed route, uniform fare, scheduled transit service to cities. London's omnibuses began in 1829, and New York City's extensive omnibus lines, starting in 1831, were operating one hundred by 1835.

Omnibuses began in New Orleans the same year as in New York City. A notice in The Courier of April 5, 1831 stated, “City and Faubourg Stage ... C. Robertson announces, on Wednesday the 6th, will run a stage from ‘The Point’ Belle Chase [sic], down [sic] to the railroad.” (“Down” here meant “to town,” but usually indicated a direction parallel to the Mississippi River's course to the Gulf of Mexico. “Up” was the opposite direction. A “faubourg” in New Orleans is a suburb or a section of the city.) Mr. Robertson's stage made three trips daily to meet Pontchartrain RR “trains” (at the time pulled by horses), leaving “Point” at 8:00, 10:30 a.m., and 3:00 p.m.; opposite trips leaving “Railroad” (Pontchartrain RR station at the foot of Elysian Fields) at 9:00 a.m., 12:00 noon, and 4:30 p.m. Fare was 25¢ for full or partial distance. The advertisement assured riders could depend upon “a strong and comfortable vehicle, careful and sober driver.”

Robertson's “stage” was both a suburban and a city service. Only a few weeks later the Lower Steam Cotton Press, located on New Levee Street several squares below the Pontchartrain RR station, began a more frequent omnibus service reaching Canal Street. Their vehicles were quickly replaced by larger models. A newspaper notice (LA 10/10/1832) stated, “Two small omnibus carriages well adapted to convey persons” at city end of the railroad (at the foot of Elysian Fields) ... “If not sold by Saturday, then will be auctioned by P. A. Guillott.” The term “omnibus” had arrived.

The new omnibuses for the Lower Steam Cotton Press were the latest examples of the carriage builders' craftmanship (LA 12/11/1832, 12/20/1832). “Two 'buses in service, named ‘The Cotton Press’ and ‘The Tobacco Plant’, both four-horse type omnibuses, replacing former 'buses”. (Already, the term “buses”, a shortening of “omnibuses”, was entering the vernacular.) This line's new 'buses established a panache for omnibus service. Each 'bus carried a letter box, forbade smoking, allowed “colored” passengers “when accompanied”. The Courier of 12/21/1832 mentioned Messrs. Carters of Newark, N. J. as the builders of these omnibuses.

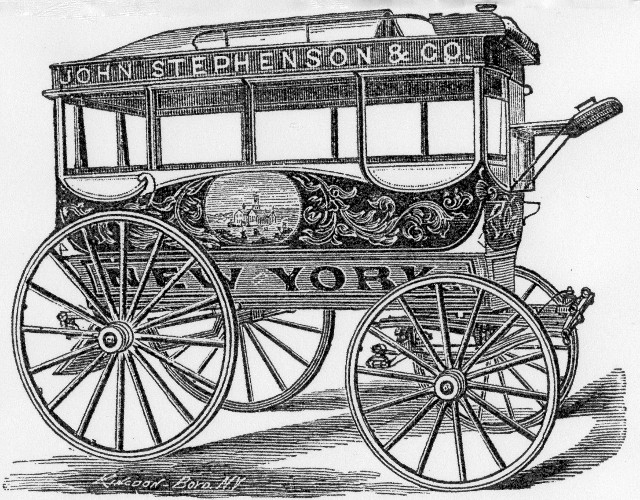

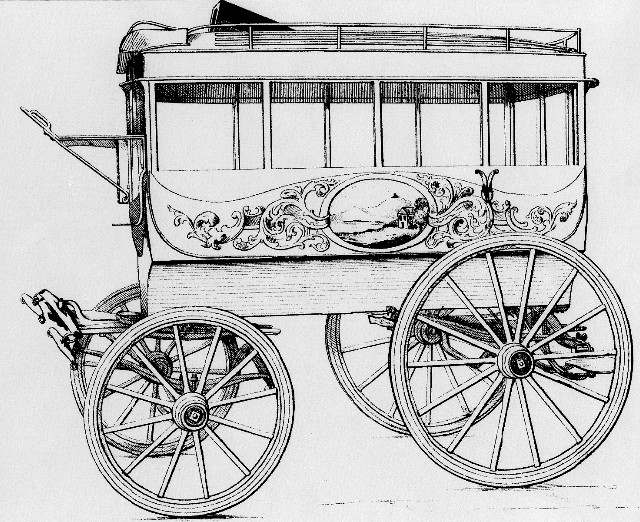

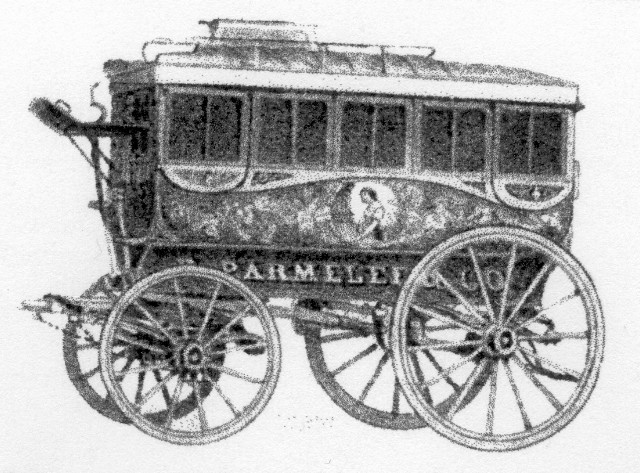

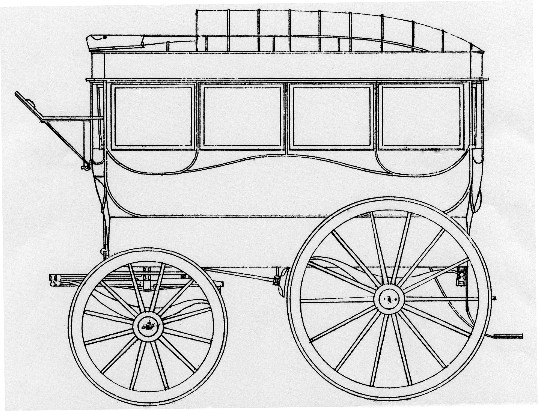

There were several U. S. carriage builders in the 1830s — the John Stephenson Co. of New York City, formed in 1831, became perhaps the largest carriage and later streetcar manufacturer of the pre-Civil War period. Others, arranged by date of incorporation (this is by no means a complete list), were: Gilbert Car Mfg. Co., later Eaton, Gilbert & Co., Troy, N. Y., 1820; Harlan & Hollingsworth, Wilmington, Del., 1836; Witbeck & Jones, Watervliet, N. Y., 1839; Laconia Car Co. (originally Ranlett Mfg. Co.), Laconia, N. H., 1844; Wason Mfg. Co., Springfield, Mass., 1845; Brownell & Wright, St. Louis, Mo., 1857; and soon after, James St. Charles Omnibus Co. of Bowanville, Ontario, Canada. These “others” built streetcars but apparently in their early years quite probably built freight haulage vehicles and omnibuses. (E. Harper Charlton, Railway Car Builders of the United States and Canada, Interurbans Special 24, Los Angeles, Cal., 1957.) John R. Stevens' research discovered order records and advertisements of the J. S. & E. A. Abbot, Concord, NH company (later Abbot-Downing). This company built stage coaches, freight haulage equipment, and omnibuses. In 1858 Mr. Slawson ordered one 12-passenger, 4-window omnibus, brilliantly painted, which reached New Orleans in 1859 — perhaps the last new omnibus the city saw for transit service.

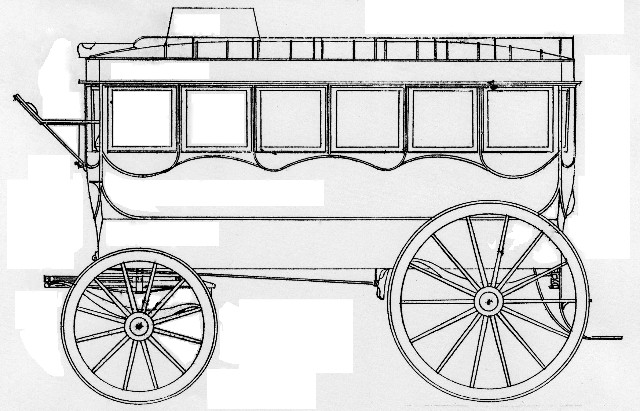

|

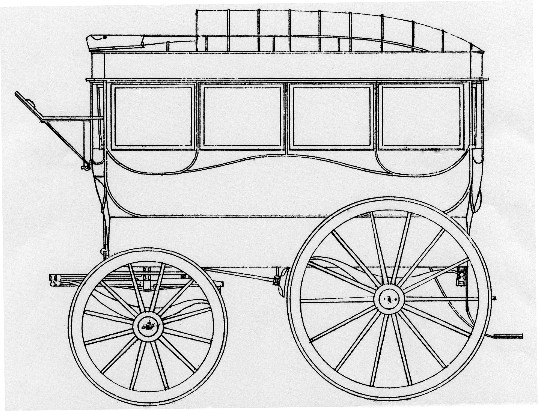

A John Stephenson omnibus. — Ezra M. Stratton, The World On Wheels, New York, 1878. |

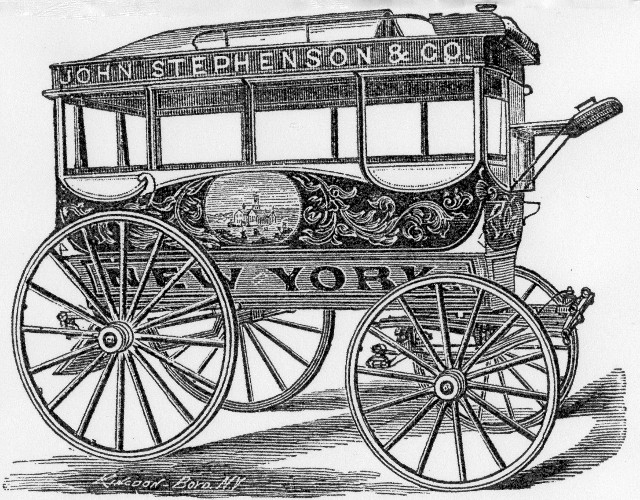

|

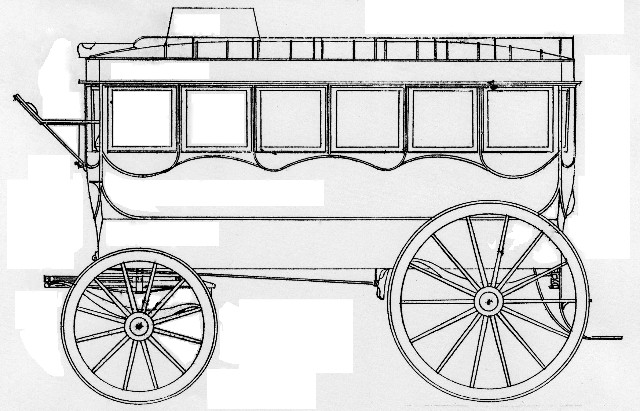

An Eaton & Gilbert model, c. 1860. — Eaton, Gilbert & Co. catalogue |

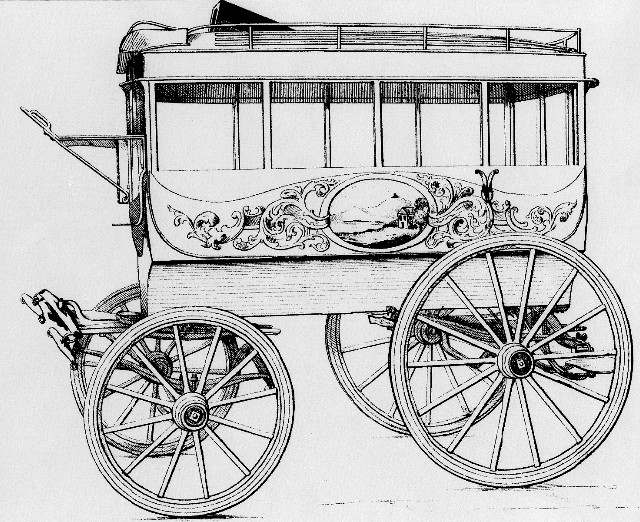

|

An omnibus from an advertisement of the J. S. & E. A. Abbot Co. of Concord, N. H. The ad included pictures of many of their products, including various models of stage coaches, wagons, and buggies. |

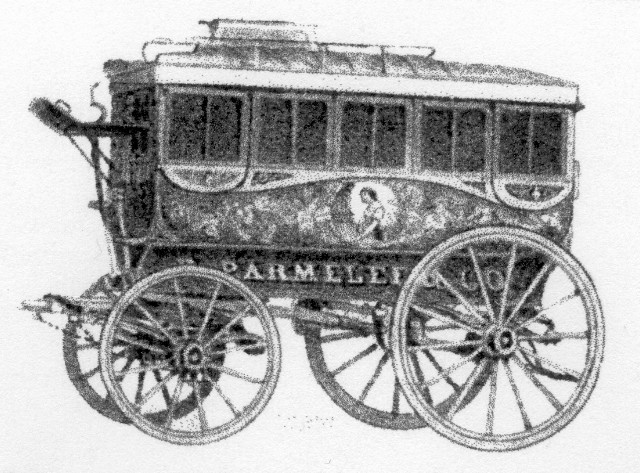

|

A four-window omnibus of the Abbott-Downing Co. This is the type that J. B. Slawson ordered in 1858. — Abbot-Downing Pattern Book, Vol. 8, New Hampshire Historical Society. |

|

A six-window omnibus of the Abbott-Downing Co. — Abbot-Downing Pattern Book, Vol. 8, New Hampshire Historical Society. |

Charles Lindaur researched and penned a brief but highly detailed treatise on omnibuses, streetcars, and their characteristics, published in the Daily Picayune of 7/30/1911, “Old time Bus-Lines and Street Cars in New Orleans”. His descriptions of omnibus details bears close reading, especially because these features were adopted by the car builders that followed and developed later modern transit vehicles.

Lindaur describes 'buses as mainly two-horse or four-horse carriages, depending on the size of the vehicles. Smaller omnibuses carried ten or twelve riders occupying longitudinal seats, with back to the 'buses sides and facing one another. Entrance was through a single door in the center rear of the 'bus. There were places on top, beside the driver, for four or more. The driver's seat was in the front, center where the roof met the front bulkhead. A strap was suspended from the ceiling, attached to the driver's boot, which when pulled signalled “stop”. There were usually two windows up front so the driver could see inside and collect fares. Soon wooden fareboxes were affixed inside just below the driver. People dropped coins in the box; the driver made change into a drawer from which the rider could collect the change. Mr. J. B. Slawson, owner of a large omnibus system, designed and patented a farebox that became one of the most commonly used in the U. S., before the Civil War.

Drivers used a whip, but not to punish or harm the horses or mules pulling the 'buses. The whip was “cracked” above the animals or tapped upon their rumps to start them. People were indignant about abuse, and a cruel driver would be excoriated in the press. At first, horses pulled the 'buses, but later mules replaced them in most operations (DP 2/1/1853).

Omnibuses had a braking system. The driver had a lever-operated system that used friction to stop. Omnibuses did not use unpaved roads, according to Lindaur. In the 1830s, New Orleans had paved many major streets with “paving stones,” heavy round-edged blocks that made a rough ride. Cobblestones were not much of an improvement. Many streets had clam shells for pavement, which gave an easier ride, but heavy rains softened the dirt. The best pavement consisted of Belgian blocks, granite brick-shaped pieces that gave a smooth ride for the 'buses. Asphalt (“asphaltum”) was mentioned in New Orleans in the 1830s (CB 6/25/1839).

A typical omnibus of the period, this one on Fifth Avenue in New York City.

The body probably seated about 10 passengers. Note the rear door, with

apparently a folding step behind. Four more passengers are standing on

the front of the roof, behind the driver, with a railing on which to lean.

The driver can just be made out in front of them; we can see his hat, an arm,

and very important, his whip. This is a two-horse model. (In New

Orleans, as elsewhere in the south, mules were generally preferred to horses,

as they were more hardy in summer heat.) — Bill Volkmer collection

A typical omnibus of the period, this one on Fifth Avenue in New York City.

The body probably seated about 10 passengers. Note the rear door, with

apparently a folding step behind. Four more passengers are standing on

the front of the roof, behind the driver, with a railing on which to lean.

The driver can just be made out in front of them; we can see his hat, an arm,

and very important, his whip. This is a two-horse model. (In New

Orleans, as elsewhere in the south, mules were generally preferred to horses,

as they were more hardy in summer heat.) — Bill Volkmer collection

Lindaur informs readers that each omnibus line had its own color, both for decorative and advertising purposes, in addition to assisting illiterate people to catch the right bus. The Apollo (now Carondelet) Street line had white livery, the same color adopted by the streetcar system that replaced 'buses on Carondelet Street (the St. Charles Street RR Co.). When an omnibus line merged with another, the colors of buyer's vehicles took over. The Apollo took yellow when merged. The Tchoupitoulas line was yellow, and the busy Magazine line adopted green.

Omnibus owners often named their vehicles, as was seen in the case of the Lower Steam Cotton Press. The New Orleans and Lafayette Omnibus Co., which started service 11/21/1833 (MA 1/13/1834), had two: the “St. Mary” and the “Delor” (named after New Orleans faubourgs). The company boasted that its “'buses have superior springs than the Lower Steam Cotton Press 'buses, for rough roads.” When Joseph Hart Hough sold his “Hough Line”, one of the Canal Street to Lafayette lines, to Philip Geiger (COB, Book 4, pp. 234-235), there were three named omnibuses: “The Washington”, “The President”, and “The Big Red”. The company had three smaller two-horse 'buses, and 40 horses to pull the vehicles. That's about six-to-one ratio, animals-to-vehicles, maybe more considering that half the fleet were small 'buses. (Street railways had a lower ratio, around five-to-one, for rails provided an almost frictionless surface for iron or steel wheels.)

Before New Orleans' railroads connected with those of the north and east, new omnibuses arrived in the big port city (the nation's second busiest) by steamship. The Daily Picayune remarked 2/2/1850 that the ship Galena arrived on the first “with omnibuses from New York” for John Hoey's Bayou Road line. These probably were John Stephenson products, or possibly Gilbert Car Co.

Omnibus companies had stations, or “stands”, where lines terminated, and riders bought tickets, obtained information, and waited. The lines had stables, where animals slept, took nourishment — even veterinarian care — and stood by for service. Animals were rotated several times daily for health and reliability. Corporations erected barns where 'buses laid over between runs, and dried out overnight after rains. 'Buses were cleaned daily, or more frequently when conditions required. Each company had personnel for maintenance, repairs, and painting. In some instances, omnibuses were actually built by the transit companies. The 'bus lines hired a goodly lot of workers, many professional, such as metal workers, carpenters, even veterinarians for the very large operations. Hoey's Lafayette Omnibus line (COB, Book 7, p. 151 — sale 2/9/1847 Philip Geiger to John Hoey) boasted 110 horses and mules and 14 “omnibus carriages”, including one being built, and one being painted. Also in the deal, a lease to a blacksmith shop and stables. Total sale: $10,000. Thus, we see a transit company building its own vehicle, a practice that became widespread in later times with the city railways.

There were city regulations governing the operation of omnibuses in New Orleans, as in other cities (Laws and General Orders of the City of New Orleans, 1857, Henry J. Leavy, p. 903). This compendium has laws and ordinances going back at least a hundred or more years. Loaded 'buses must move no faster than a horse's walk, and without passengers, no faster than a “trot or pace”; loaded or not, 'buses can take turns no faster than a walk. Omnibuses must be numbered “in a conspicuous place.” Violations brought a fine of $25. The same was the cost of a license, one for each 'bus. The city levied a modest tax against omnibus earnings, but apparently no ordinances were required for establishing routes, and heavily used routes, such as Magazine St., may have had competing operators.

The usual operating problems burdened the 'bus lines, as they do with today's rail and bus transit. Weather conditions, breakdowns, sudden crowds, unruly passengers, vehicle accidents, vehicle maintenance, cleanliness, maintaining schedules — to name a few. But, with animal powered transit systems, besides the care and health of horses and mules, there was one almost unbelievably ponderous problem: what to do with the accumulation of manure. It wasn't easy to sell, because everyone had animals — farmers certainly had enough fertilizer. Hoey's Lafayette line had 110 horses and mules — even a five-pound output per animal, per day, would make a ton in about half a week! The pile would be a spawning ground for sky-darkening swarms of flies. That, in the era before window screens, would wreck any quality of life there was. This was something no one praising “the good old days” could be knowing!

Copyright © 2014 Louis C. Hennick. All rights reserved.

Computer Science Department, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Home Page